Andy Gambaccini recently was interviewed in connection with a Massachusetts Lawyers Weekly article discussing a Cambridge police officer’s civil rights lawsuit alleging that his free speech rights were infringed when his employer issued a four-day suspension following the a Facebook post from the officer.

While the full story is below, the portion featuring Gambaccini is excerpted here:

Worcester lawyer Andrew J. Gambaccini, who represents law enforcement officers in civil rights cases and other matters, emphasized the difficulty of balancing the competing interests in cases involving the free speech rights of public employees.

“On one side of the ledger, public employees possess the ability to speak freely. But, given their decision to accept public employment, that ability is diminished,” Gambaccini said. “On the other side, public employers have an interest in maintaining the effectiveness of their undertakings, including avoiding the problems inherent in the actual or perceived misconduct of employees, but that interest only may extend as far as the impact on business goes.”

Gambaccini said he foresees the balancing of interests to become more complicated as Hussey’s case proceeds. “While the constitutional question here was difficult, it only will become thornier when a summary judgment record is developed,” Gambaccini said. “It is not easy to quantify the impact on governmental operations occasioned by an employee’s speech.”

Officer disciplined due to George Floyd comment can sue

City claims Facebook post undermined public trust

By: Pat Murphy October 21, 2022

A Cambridge police officer can sue the city for violating his free speech rights by disciplining him over a Facebook post critical of the efforts of Democrats in Congress to honor George Floyd, a U.S. District Court judge has found.

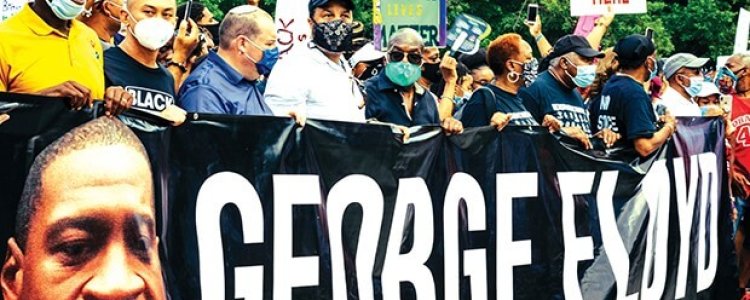

In February 2021, Officer Brian Hussey posted a news article on his personal Facebook page concerning the plans of certain House Democrats to reintroduce a police reform bill named in honor of George Floyd. The 46-year-old Black man died in May 2020 when a Minneapolis police officer restrained him by kneeling on his neck. The incident provoked a summer of sometimes violent protests across the country. Derek Chauvin, the officer directly responsible for Floyd’s death, was later found guilty of second-degree murder, third-degree murder, and second-degree manslaughter.

Hussey’s post included the comment: “This is what its [sic] come to ‘honoring’ a career criminal, a thief and druggie … the future of this country is bleak at best.”

When Hussey’s superiors were made aware of the post, he was placed on administrative leave and later received a four-day suspension.

Hussey sued the city under §1983, claiming that the discipline violated his right to free speech under the First Amendment. The city responded with a motion to dismiss, arguing that, as a police department employee, Hussey’s free speech rights were limited and that the discipline was warranted because the Facebook comments undermined the public’s trust in the department.

But Judge Angel Kelley found that the lack of a developed factual record concerning the validity of the city’s justifications for discipline rendered dismissal premature.

“While Hussey’s post could undermine the community’s trust in the CPD and relationships between officers, resulting in ‘significant disruption and inefficiency,’ the Court cannot, based on the facts in the complaint before it, definitively resolve the close constitutional question of whether ‘such a risk’ outweighs the interests served by Hussey’s speech,” Kelley wrote.

The 13-page decision is Hussey v. City of Cambridge, et al., Lawyers Weekly No. 02-338-22.

Overreach by Cambridge?

Harold Lichten, who represents Hussey, said he and co-counsel Benjamin Weber agree that police officers have special obligations not to incite violence “or say derogatory things that may inflame passions,” but they also have the right to speak their mind about issues of public concern.

Central to his client’s case, Lichten said, is the fact Hussey in his Facebook post was not commenting about the murder of George Floyd or whether Minneapolis police acted properly.

“The city of Cambridge being the city of Cambridge thought [the Facebook post] was so ‘un-woke’ that they needed to suspend him for four days for one comment that was posted for two hours.”

— Harold Lichten, Boston

“His whole focus — and I think this is where the city went off the rails — was whether it was proper for Congress to name a federal law in honor of someone who had a pretty bad history of both criminal activity and drug use,” the Boston lawyer said. “The city of Cambridge being the city of Cambridge thought that was so un-woke that they needed to suspend him for four days for one comment that was posted for two hours.”

But Boston attorney Leonard H. Kesten disagreed with the notion that the Cambridge Police Department could simply overlook Hussey’s Facebook post.

“It’s a very inflammatory comment that would create a lot of problems for any police department dealing with their population,” said Kesten, who represents police officers as part of his practice.

“You’re a police officer; you do have to have the trust of the population.”

“It’s a very inflammatory comment that would create a lot of problems for any police department dealing with their population. You’re a police officer; you do have to have the trust of the population.”

— Leonard H. Kesten, Boston

Douglas I. Louison, a municipal and civil rights attorney in Boston, said he thought the judge made the right call in allowing the plaintiff’s case to go forward.

“Officers are subject to review of their social media when they identify themselves as police or use indicia of their departments,” Louison said. “But in this case, it seems like [Hussey] was acting as a private citizen opining his private point of view.”

Worcester lawyer Andrew J. Gambaccini, who represents law enforcement officers in civil rights cases and other matters, emphasized the difficulty of balancing the competing interests in cases involving the free speech rights of public employees.

“On one side of the ledger, public employees possess the ability to speak freely. But, given their decision to accept public employment, that ability is diminished,” Gambaccini said. “On the other side, public employers have an interest in maintaining the effectiveness of their undertakings, including avoiding the problems inherent in the actual or perceived misconduct of employees, but that interest only may extend as far as the impact on business goes.”

Gambaccini said he foresees the balancing of interests to become more complicated as Hussey’s case proceeds.

“While the constitutional question here was difficult, it will only become thornier when a summary judgment record is developed,” Gambaccini said. “It is not easy to quantify the impact on governmental operations occasioned by an employee’s speech.”

Defense attorney Kate M. Kleimola, of the city of Cambridge’s law department, did not respond to a request for comment.

Controversial Facebook post

According to court records, the plaintiff has worked as a police officer for the city for 24 years. He maintains a private Facebook page that does not identify him as a Cambridge police officer.

Hussey posted his George Floyd comment while he was off duty after reading a story by a local news outlet with the headline: “House Democrats Reintroduce Police Reform Bill Named in Honor of George Floyd.”

The plaintiff took the post down approximately two hours later as was his normal practice.

Hussey explained his motivations behind the post in his complaint. According to the plaintiff, while he supports police reform and “believed strongly that the individuals responsible for Floyd’s death should be prosecuted criminally,” he was concerned “as a private citizen that an important act of Congress would be named ‘in honor’ of someone who was reported to have a criminal record, included aggravated robbery during a home invasion, and history of drug abuse.”

Hussey v. City of Cambridge, et al.

THE ISSUE: Could a Cambridge police officer sue the city for violating his free speech rights by disciplining him over a Facebook post critical of efforts by Democrat members of Congress to “honor” George Floyd?

DECISION: Yes (U.S. District Court)

LAWYERS: Harold Lichten of Lichten & Liss-Riordan, Boston; Benjamin Weber of Boston (plaintiff)

Kate M. Kleimola of the city of Cambridge law department (defense)

In March 2021, the police commissioner informed Hussey that he was being placed on administrative leave because of the Facebook post. The plaintiff was on administrative leave for two months before receiving a four-day suspension.

In November 2021, the plaintiff filed his §1983 action. In addition to naming the city as a defendant, the plaintiff sued the commissioner both in his individual capacity and in his capacity as police commissioner. In her ruling, Kelley found that the commissioner was entitled to qualified immunity.

Balancing act

Addressing the city’s motion to dismiss, Kelly was guided by the so-called “Pickering test.” The three-part test was formulated under two U.S. Supreme Court decisions addressing free speech in the public employment context: the 1969 decision in Pickering v. Board of Education and Connick v. Myers, handed down in 1983.

Under the Pickering test, the question of whether a government employer violated an employee’s right to free speech by taking an adverse action against him depends on whether: (1) the employee spoke as a citizen on “a matter of public concern”; (2) the employer had an “adequate justification for treating the employee differently from any other member of the general public,” defined by whether the interests of the employee and public “outweigh the government’s interest in functioning efficiently”; and (3) the protected speech was a “substantial motivating factor” in the adverse employment action.

In Hussey, the parties did not dispute the first and third elements. Addressing the second Pickering factor, Kelley wrote that, in light of the impact of George Floyd’s murder on society, “Hussey’s Facebook post spoke broadly to several topics — use of force by law enforcement, police reform, and racial justice — on which ‘free and open debate is vital to informed decision-making.’ Viewed in that light, the value of the speech is high, as the public ‘also had a non-trivial interest in the information’ conveyed.”

On the other hand, the judge was troubled by the tenor of the plaintiff’s comments.

“Here, Hussey ‘put [the] pejorative labels’ of ‘career criminal,’ ‘thief,’ and ‘druggie’ on George Floyd, a victim of murder at the hands of those obliged to protect and serve the public, and whose unjust death sparked a global movement calling for police reform and racial justice,” Kelley wrote. “Employee speech that is done in a ‘vulgar, insulting, and defiant’ manner is generally ‘entitled to less weight in the Pickering balance.’”

Turning to the city’s interest in regulating employee speech, Kelley wrote that the 1st U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals has recognized that the government’s interest is “particularly acute” in the context of law enforcement, where there exists a “heightened interest” in maintaining discipline and harmony among employees.

Kelley found that the city had legitimate concerns that Hussey’s Facebook post “had the potential to damage CPD’s reputation and to undermine the community’s confidence in CPD’s willingness to fulfill its duty to protect all members of the community and respect the constitutional rights of those in its custody.”

Nonetheless, Kelley concluded that, given the current state of the record, she was unable to ascertain whether the city’s predictions about the risk of disruption posed by Hussey’s post were reasonable.

“Hussey’s complaint does not allege that any actual disruption or harm resulted from Hussey’s Facebook post, nor do the defendants describe any such consequences,” Kelley wrote. “There is nothing to indicate that Hussey’s Facebook post was reported by local media, undermined CPD outreach to the community, violated any CPD policies or diversity initiatives, all of which could support the government’s prediction that Hussey’s speech would harm its strong interest in maintaining the public trust and a bias-free police department.”

Given the court’s obligation at the dismissal stage to “indulge all inferences in favor of” Hussey, Kelley concluded that the complaint sufficiently stated a plausible claim to relief and overruled the city’s motion to dismiss.